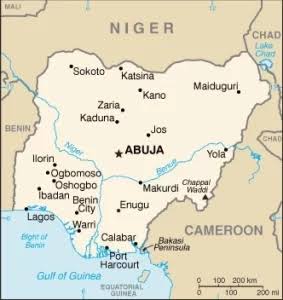

The tragic wave of violence unfolding in Benue State has many faces: mass killings, forced displacement, and a humanitarian emergency. But there is an often-overlooked dimension that binds conflict and climate together — the way environmental change amplifies the risk of violence, and how violence deepens climate vulnerability. Here, we unpack the climatic effects of what many are calling a genocide or systematic campaign in Benue, why they matter, and what must be done.

The Crisis: Genocide, Land-Grab, and Disruption

Across Benue State, communities have endured violent attacks, mass displacement and loss of livelihoods. For example:

The Yelwata massacre saw around one hundred people killed in June 2025.

Indigenous leaders describe the pattern not as random clashes but as a “well-calculated … full genocidal land grabbing campaign” aimed at farming communities.

The term “genocide” is used by diaspora groups and civil society highlighting the scale and targeted nature of violence.

These acts devastate both human lives and the agricultural base of the state — widely known as Nigeria’s “food basket.” Farms destroyed, farmers displaced, livestock scattered, and communities degraded.

Climate & Environmental Context: The Underlying Stress

Conflict in Benue doesn’t occur in a vacuum. There are deeply rooted climatic and environmental pressures that fuel tensions:

A study in Oju Local Government Area found that 79.6% of respondents agreed that floods had increased during the rainy season, and 84.8% agreed that yields were falling because of high temperatures and low rainfall.

Research on farmer-pastoralist conflict argues that changing rainfall patterns, shifting grazing routes, and degraded land in northern Nigeria push herders southwards — placing pressure on land and water in Benue.

Benue’s status as a fertile agricultural hub is under threat: flooding risk is increasing and displacement reduces the capacity to farm.

Thus, climate change and environmental degradation are not just background themes — they are active ingredients in the conflict.

How the Violence Amplifies Climatic Vulnerability

The interplay between violence and climate in Benue sends several dangerous signals:

Loss of Agricultural Production

With farms destroyed or abandoned, agricultural output falls. One academic study found that insecurity in Benue led to a statistically significant drop in both crop and livestock output.

This reduces food security, increases dependence on imports and raises poverty levels.

Displacement and Loss of Land Stewardship

Thousands of people have fled their homes. Displaced farmers cannot tend their lands, implement climate-resilient practices, or maintain ecological buffers like soil cover and water systems.

Vacated land may degrade, become over-grazed, or converted in unsustainable ways.

Resource Scarcity and Competition

The violence over land and grazing is worsened by shrinking resources (water, grazing land, arable land) caused by climate shifts.

As environmental pressure rises, so does likelihood of conflict — a vicious cycle.

Floods, Erosion & Infrastructure Damage

Flood forecasts highlight Benue’s vulnerability. But in war-affected zones, communities are less able to invest in flood defences, drainage, early warning, or land-management systems.

The destruction of homes or displacement increases exposure to natural hazards.

Why This Matters Nationally & Internationally

Benue’s decline threatens Nigeria’s food security: when “the food basket” suffers, the ripple is felt across states and markets.

Climate change is global, but its worst impacts often hit the poor and the insecure — amplifying justice concerns.

Addressing violence and climate separately is insufficient; the two are intertwined and must be tackled together.

Pathways Ahead: What Needs to Be Done

To respond to the double-threat of genocide-style violence + climatic degradation in Benue, a multi-pronged strategy is required:

Security & Protection: Immediate protection of vulnerable communities, enforcement of laws on open grazing, disarmament of militias.

Climate-resilient Agriculture & Water Management: Support farmers to adopt resilient crops, improve irrigation, manage floods and droughts. (as suggested by Oju study)

Resource Governance & Land-Use Planning: Clarify and enforce land rights, grazing routes, water access — reducing competition that triggers violence.

Integrated Early Warning Systems: For both conflict (e.g., patterns of attacks) and climatic hazards (floods, droughts) — communities must be alerted and prepared.

Displacement Management & Community Rebuilding: Assist displaced persons, restore productive land use, rebuild infrastructure and ecological buffers.

Data, Research & Accountability: More rigorous monitoring of agricultural loss, displacement, violence and climate impact — to support evidence-based policy.

Conclusion

The tragic events in Benue State are not simply about ethnic violence or herder-farmer clashes — they sit at the nexus of violence + environmental stress. Climate change has altered the ground beneath the conflict, and the conflict now accelerates climate-hurt and ecological fragility. What we are witnessing aligns with what many call genocide — and if we ignore the environmental dimension, we miss a huge piece of the puzzle.

The message for social-media and wider public debate is clear: peace in Benue requires climate justice, agricultural revival and protection of communities. Anything less will leave the territory of Nigeria’s food basket bleeding — and the climate costs mounting.